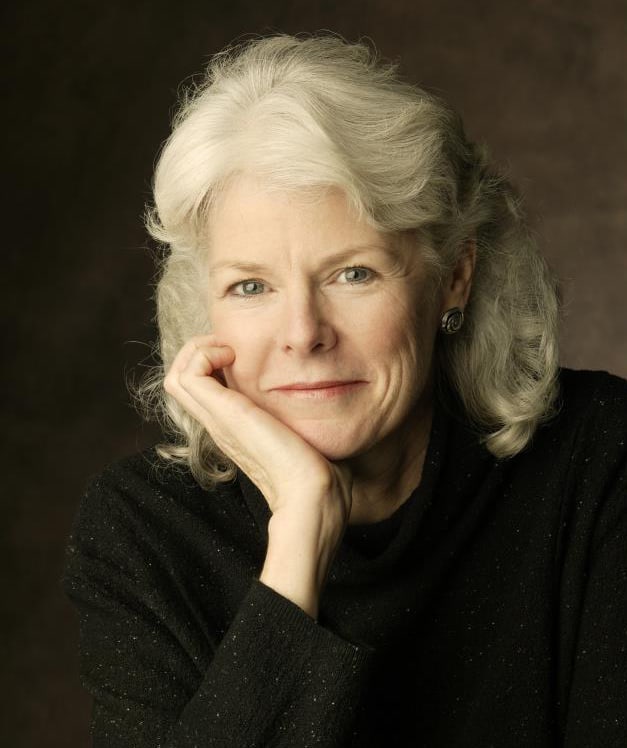

Defining Your Own Sacredness with Barbara Brown Taylor

I am so honored to bring you this recent interview with one of my favorite writers and thinkers, Barbara Brown Taylor. Barbara is an ordained Episcopal priest and the New York Times–bestselling author of the memoir Learning to Walk in the Dark, a gorgeous guide to finding our spirituality in times of difficulty. Barbara says that she wrote it as “a way of asking readers to think twice before they sign on to the kind of spiritual duality that pits light against dark, body against soul, and us against them.”

I was most impressed by Barbara’s truth and authenticity, which came through bright and clear in her beautiful, powerful words. Her candor, her ability to find beauty in the little moments, and her reliance on uncertainty as a tool for discovery all resonated deeply with my own heart.

In this conversation, Barbara also shares what she believes when she hears the word “sacred,” as well as her personal vision of the feminine in the often male-dominated world of the church. Much like the people she most admires—truthtellers whom she loves being around “because I never have to wonder what they’re thinking, and they never make me feel small”—Barbara is someone who invites curiosity, honesty, and playfulness.

I especially loved her take on being in the business of reflecting on questions rather than coming up with definitive answers. When it comes to matters of faith and spirituality, she says, “I think every person has to come up with the answer for him or herself. Why would you want mine when your own is out there waiting for you?”

I hope you love reading this conversation as much as I loved being part of it!

Can you tell us the one experience in your life that most defined who you are today?

That would be a hard question, even if you asked me for the one experience that defined each decade of my life! But there is a time that stands out because it delivered a lasting truth—one that has stayed true through all the changing circumstances of my life.

I was in my twenties, studying for a graduate degree in divinity without any idea what I would do with it in the end. All of my classmates seemed so much more mature and focused than I was. They knew where they wanted to go in their lives and the steps they had to take to get there. All I knew was that I wanted to know more about God, and that I liked being with people who wanted to know the same thing.

There was an abandoned Victorian mansion next door to the divinity school that had once housed the Culinary Institute of America, but the Institute had moved on and the university hadn’t decided what to do with the property yet. I loved walking around over there after dark, and the top landing on the three-story fire escape was one of my favorite places to pray. I could see the whole city from up there, and no one could sneak up on me without me hearing first.

So on the night I am thinking of, I begged God to tell me what to do with my life—to give me some clear direction I could follow, or at least a nudge in the right direction. I really, really wanted to know what I was supposed to be doing, and I was ready to accept any answer. If God wanted me to go halfway around the world and dig latrines, I was ready to do it. If God wanted me to get a Ph.D. and teach college, I was ready to do that, too. I just wanted an answer—and I got one!—but not at all what I expected.

While I was straining to hear God’s voice, this thought came into my head that I did not recognize as my own thought, because what it said to me was so different from anything I would have thought to say to myself. It said, “Do whatever pleases you, and belong to me.” Since those words were for me, not anyone else, I don’t expect them to hit anyone else the way they hit me, but the effect on me was divinely liberating.

God set me free to do anything I wanted to do, as long as I did it in a godly way. At last count, I have had ten different jobs since then—all of them interesting, all of them offering me the chance to relate to other people in life-giving ways—and thanks to that night on the fire escape, I have always felt like I was in God’s embrace.

How do you define authenticity in your own life and act on it (and who are your models of authenticity)?

My models of authenticity are people you have never heard of, but what they all have in common is a high degree of continuity between their convictions and their actions. They are proven truthtellers, who do what they say and aren’t afraid to say when they have gotten something wrong. Their hair may not always be combed, and they may not have the best-speaking voices in the world, but how they look and sound matches up with what they say and write. They either don’t know how to dissemble, or they don’t have time for it. I love being around them because I never have to wonder what they’re thinking, and they never make me feel small. In my own case, I’m afraid that “being authentic” means “doesn’t have appropriate filters.” I was raised by wolves. No one ever taught me to conceal my true thoughts or feelings.

You are an Episcopal priest whose book about leaving the church really struck a chord among lots of readers. What was the moment of truth that made you decide to leave the church, and how did you reclaim faith on your own terms?

I celebrated the 32nd anniversary of my ordination earlier this year. I probably should have titled my book Leaving Parish Ministry instead of Leaving Church, since that is more accurately what I did.

After 15 years of full-time ministry in two different congregations—one in a big city and one in the small town where I still live—I hit a wall I could not budge. Sometimes I think it was the extroversion of the job that did me in. I would have made a very happy librarian. Other times, I think it was the professional nature of the job that did it. Loving and serving people is one thing, but getting paid to do it is quite another.

The short answer is that the public and professional requirements of the job took so much time that I didn’t have enough time left to care for my own soul. I think the moment of truth came when I started crying on the porch of the church after worship while I was shaking people’s hands. I didn’t know where the tears were coming from. I thought I had an allergy, which is what I told people when they started fishing around in their pockets and pocketbooks for a handkerchief. But it wasn’t an allergy. It was a grief so deep that I didn’t even have words for it.

The story has a happy ending, though. I love teaching college, which I never thought was possible for me without a Ph.D. I have been at it for almost 20 years now, and I still get excited when a new semester rolls around. The classroom has made it possible for me to reclaim faith on my terms, by releasing me from the answer business and getting me into the question business, instead.

How do you define “sacred”? How can we create sacredness in the midst of our daily lives?

If I defined “sacred” for you, then you won’t have a chance to define it for yourself, and I think that’s very important. But since you’re in charge here, I’ll try.

I use the word “sacred” to describe something that grounds me in this world and opens me up to another world all at the same time. Oceans usually do it, especially in the middle of summer storms. The kindness of strangers does it. Getting sick does it, especially if I am so sick that I cannot do anything for myself. Being present at the birth of a new human being does it, and so does being between the sheets with someone I love. I could go on.

I use the words “holy” and “divine” to describe the same phenomena. They almost involve the sense that there is a Witness to my life, a Consciousness that is for me in the best situations but also in the worst, where this Sacredness is working around the clock to make life out of death for me and every other living thing.

Sometimes I think that believing this is what makes it so. The more I look for it, the more I see it. I wrote An Altar in the World for people who kept asking me questions about what I meant, but in the end I think every person has to come up with the answer for him or herself. Why would you want mine when your own is out there waiting for you?

In your book Learning to Walk in the Dark, you talk about how we can connect spiritually when we don’t have all the answers. You encourage readers to embrace uncertainty. Can you say a little more about that?

Sure. Most authors write the book they most need to read, and I am no exception. Since I left parish ministry and have begun really asking questions about what I believe to be true, I have had less and less to say. I used to have a lot more to say, but in retrospect a great deal of it was hearsay—things other people had told me were true, and told me I had to believe were true whether they made any sense to me or not.

Don’t get me wrong—I’m still willing to believe things that don’t make rational sense (like “there is a Witness to my life”)—but the truths I care about these days don’t come in the form of propositions. They come in the form of relationships, and relationships are so fluid that the truth in them shifts from one moment to the next. So I don’t have a lot of religious certainties anymore. What I have, instead, are richer relationships—with people of many faiths and none—who are willing to feel their ways along with me although neither of us knows for sure where we are going.

The uncertainty causes us to take great comfort in each other’s company. It also seems to make us braver. When I look back at my life, it is clear that what I most needed to know was hidden in the places where I least wanted to go. “Darkness” is my reigning metaphor for those places. I’m not saying it’s safe to go into them. I’m just saying it’s necessary.

I think that the reason so many people cling to institutional religion (and institutions in general) is a deep-rooted fear of change. Religion promises something that’s permanent and eternal. But how have you incorporated change into your own spiritual beliefs?

Institutional religion has a lot going for it: hospitals, neighborhood clinics, schools and colleges, orphanages, retirement homes, food kitchens, and international service projects, just to name a few. Who will fund these things when the “nones” and “dones” outnumber the old guard?

But yes—religious institutions are essentially conservative. Their job is to conserve the wisdom of the ages and make sure it is delivered from generation to generation without too much sand leaking out of the bag, and that can translate into a fear of change. At its best, religion promises contact with something or someone that transcends the present moment. The catch is that you can’t box the transcendent. It’s bound to escape every pen you build for it.

So a religion also has to be good at giving people worthwhile things to believe and do while they are in the present moment, and that requires change. All the living religions in the world today are still alive because they met the challenge of change. The ones that didn’t or couldn’t are gone. Since I teach world religions at the college level, I have almost daily opportunities to explore, amend, and extend my spiritual life. I can’t teach the central beliefs and practices of the world’s great religions without admiring a lot of them and trying them on for size. Two weeks ago I was invited to participate in jumma for the first time—the Muslim Friday prayer service. I have always wondered what it feels like to pray with one’s whole body like that. Now I know!

You also mention that our tendency to conflate light with good and evil with darkness is too simplistic, even dangerous. And you talk about lunar spirituality vs. solar spirituality. What do you mean by that?

You will have to read the book to find out! If you have ever been sunburned, then you know there is such a thing as too much light, and if you have ever swapped secrets in the dark with someone you love, then you know that darkness has a lot going for it.

The book builds on experiences like those and many others, as a way of asking readers to think twice before they sign on to the kind of spiritual duality that pits light against dark, body against soul, and us against them.

I think we are seeing a surge of women who are unsatisfied with church doctrine because it does not feel inclusive of the feminine. What are your thoughts about the “sacred feminine” and its place in organized religion, as well as your own personal spirituality?

From my own vantage point, I see churches being changed in significant ways by the leadership of women—especially small rural churches that cannot pay the kinds of salaries that attract men. While there are certainly denominations that do not ordain women, the student body of the seminary I attended is now 50% women, and that seems to be the norm in most mainline Protestant seminaries.

At the same time, there is no getting around the fact that Christianity was born in a world where the masculine was ascendant and the feminine was assigned to serve. So yes, one tires of calling God “Father” and wondering where the Mother went. That is why it is so important to have women in ministry—because they embody the sacred feminine that is missing from much of scripture and tradition.

Mary plays a huge part in my own devotional life—and not just the Mary with a baby in her arms, either. My favorite religious object is a wooden statue of Mary that I brought home from Ecuador. I think they call her the Virgin of Quito. This particular image of her comes from the twelfth chapter of Revelation: “a woman clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet, and on her head a crown of twelve stars.” She is wearing a blue gown studded with gold stars. Her loose hair is flowing down her back. She is holding a leash in her hand, and if you follow it down to the moon under her feet, you can see the head of the dragon she has tamed. She is my ideal image of the sacred feminine, and I take pleasure in her every single day.

What inspires you personally?

The music of Bach, the students in my classes, the Dingle Peninsula in Ireland, my sister’s courage in the face of stage four cancer, three shelves of poetry in my library, a really good dinner party, the regular return of spring, watching chicks peck their way out of eggs, the view from my front porch, losing five pounds, watching my Jack Russell terrier chase a deer with full confidence he can catch it (though he never has), and seeing my 79-year-old husband perform a perfect Warrior III pose in yoga class.

What one piece of advice do you have for the Women For One community?

You already have everything you need.

1 comment to "Defining Your Own Sacredness with Barbara Brown Taylor"